Revisiting the Ostwall

The last visit to the Ostwall — an underground fortification system in Poland built by the Nazis to defend against a Russian invasion — was so impressive that it was high time to return.

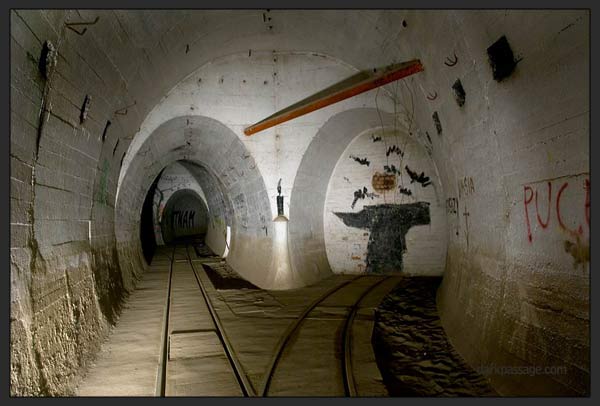

Germany began building the system in 1935 with a planned length of around 80 miles (second only to the Maginot line) at a depth of about 70 feet beneath the bucolic countryside. About 20 miles of underground tunnels were finished, with a rail line, machine shops, munitions warehouses, hospitals and barracks. After WWII, much of the system was ransacked and destroyed.

Back in 2002, a detailed map of the various entrances, in the form of partially imploded stairwells and bunkers, would lead to any number of treacherous but viable access points. At the time of that first visit the underground passages were a destination for military geeks, tunnel explorers and locals, who would descend on weekends to spraypaint and drink beer.

Sure, it was a dangerous place to visit and some people died, plunging down uncovered shafts, missing their step on crumbling staircases and, in one case, burning to death in a small chamber. But instead of sealing up the system, the sites of death were marked with a cross. There is no greater warning system. If you peer down a shaft and see a cross all the way down there in the beam of your flashlight, your blood runs cold. Fences will be climbed but crosses are respected.

Now, unfortunately, that same trusty map yields one sealed bunker after another. It’s quite a feat to weld metal bars across a hole in the ground in the middle of a forest. It’s also quite a feat to still find access to the underground labyrinth. About 20 bunkers were visited – some take an hour or so to hike to from a dirt road – until one was found with a missing metal bar, leaving just enough space to squeeze through and then balance on a wooden log over an open pit before finding the staircase down.

But suddenly, once you’ve arrived, you can be pretty sure that you’re the only one down there. Miles of tunnels below the countryside all to yourself.

Whereas before, given enough time, you might have run into a tagger, now that the tunnels are sealed off, the murals have become a strange kind of time capsule.

The graffiti is the only sign remaining of any tenuous human occupation, the only trace of this kind in the entire complex. The Nazis left it barren and stark — like a strange underground spaceship with its ovary shapes and gleaming grey concrete, something that was never meant to be part of this earth.

The graffiti has sabotaged this unearthliness almost with a kind of desperation, a frantic attempt to obliterate the inhuman blank spaces. This echo of voices and gestures lends a measure of comfort to someone passing through, someone who is acutely aware of the utter desolation and remoteness of the site.

But knowing that the few stairwells are blocked, and — very far away — there is only one known way out, the illusion of companionship fades rather quickly. You’re navigating this egg-ship by yourself. Just be sure you remember the position of the sun.

Comments are closed.